Characteristics of intervals – Inversions

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

Inversions

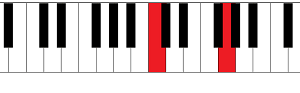

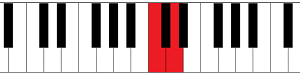

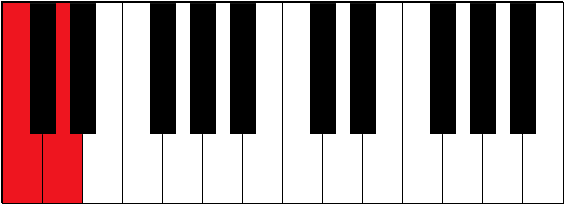

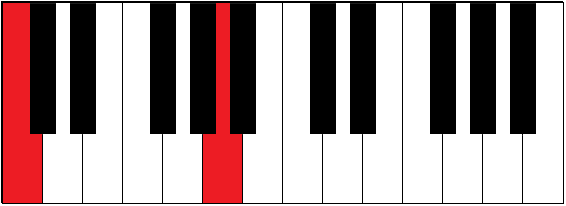

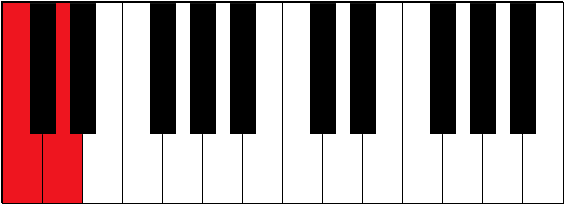

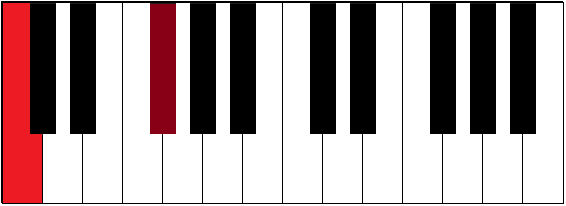

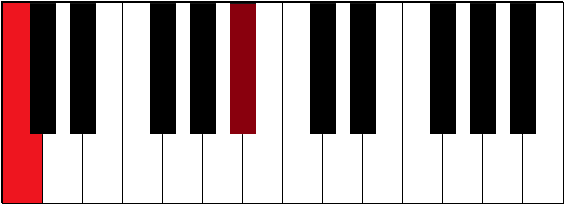

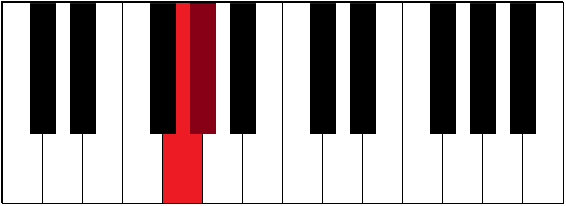

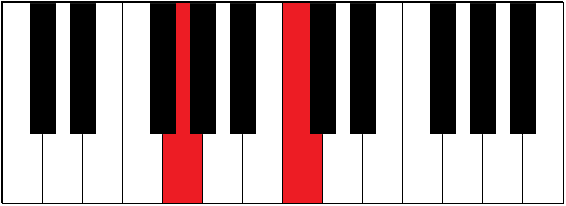

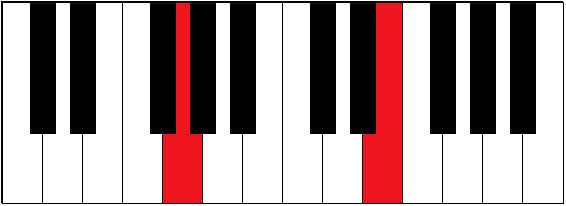

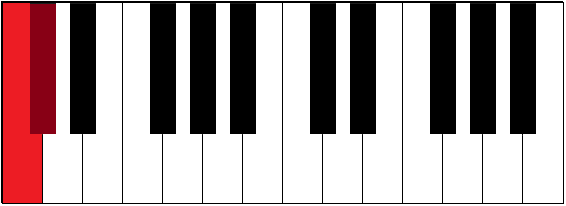

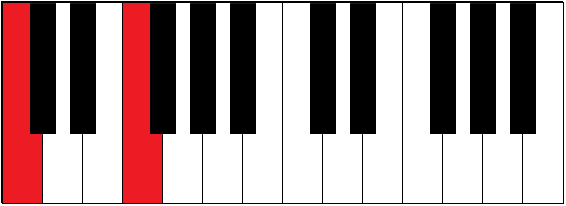

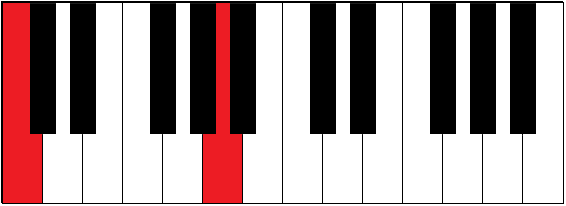

Let me start with the example of the perfect 5th interval from C to G, as indicated on the next keyboard:

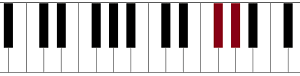

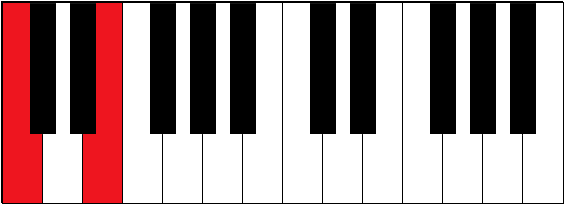

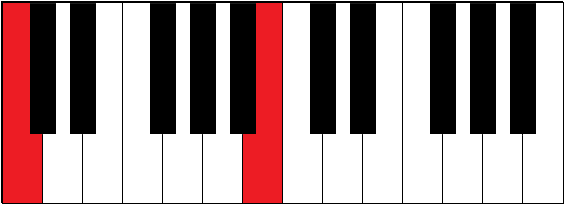

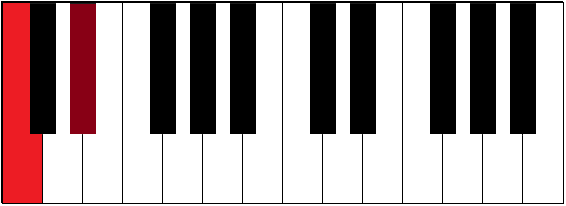

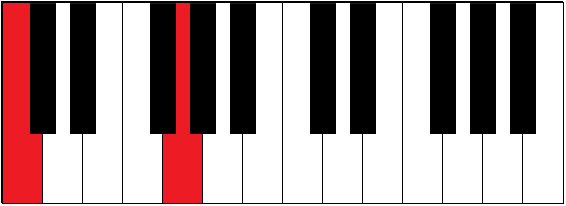

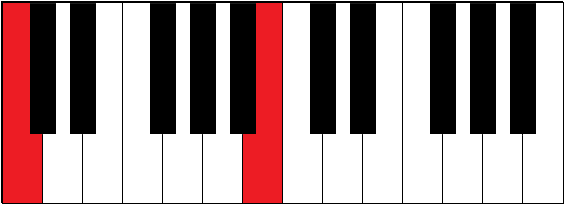

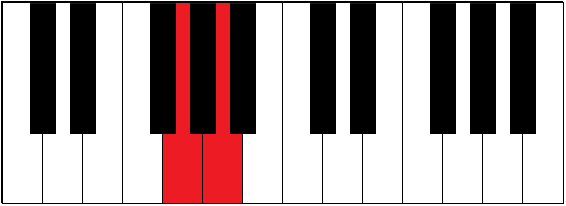

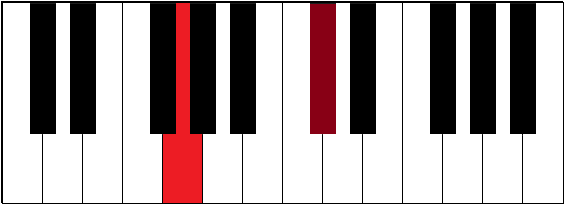

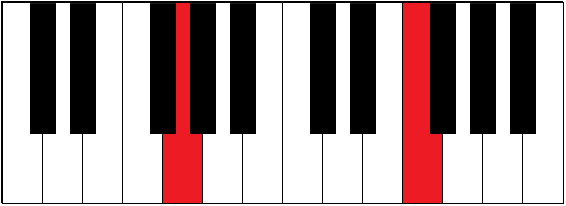

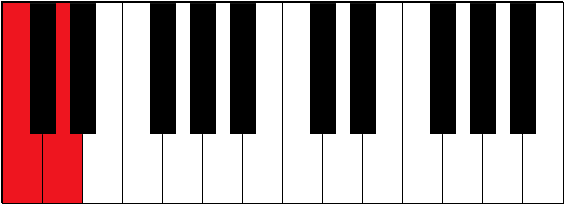

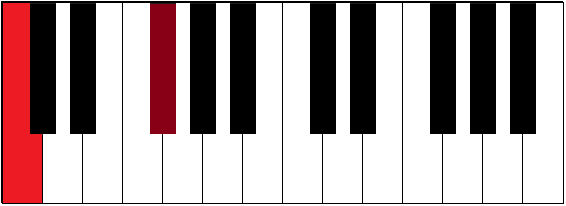

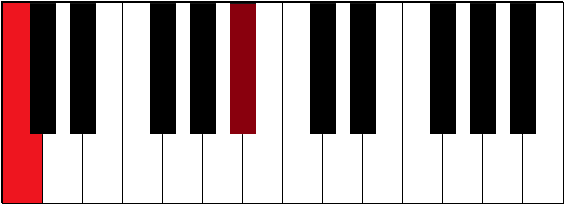

You can make an inversion of this perfect 5th interval by either taking the highest note and move it an octave down, or by taking the lowest note and move it an octave up. In the keyboard below, you see the highest note that was moved an octave down. Whether you move the highest note an octave down, or the lowest note an octave up, the result is the same: the inversion of the perfect 5th interval from C to G is a perfect 4th interval from G to C.

So, a perfect 4th interval is the inversion of a perfect 5th interval. The reverse is also true: a perfect 5th interval is the inversion of a perfect 4th interval. Together they add up to an octave, because a perfect 5th (7 semitones) plus a perfect 4th (5 semitones) make together 12 semitones, an octave.

You can also see it the following way: when you want to go from C to G, you can either go up a 5th, or go down a 4th.

Inversions of other intervals

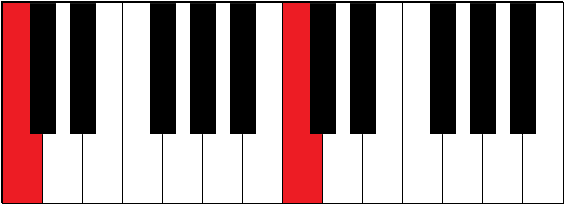

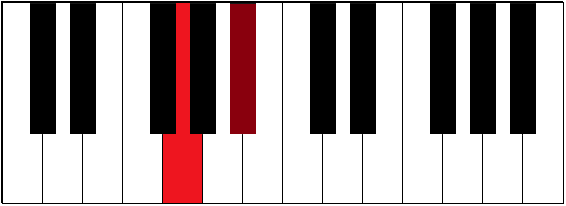

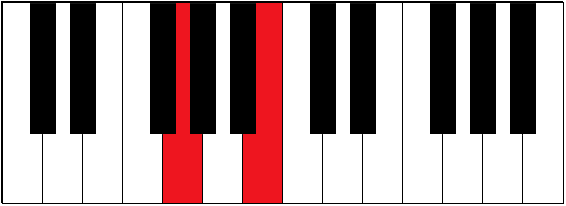

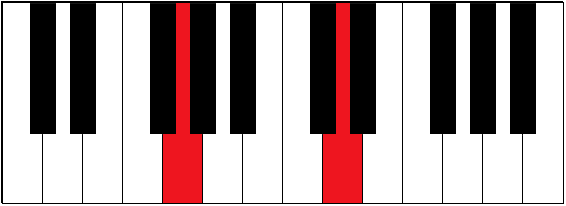

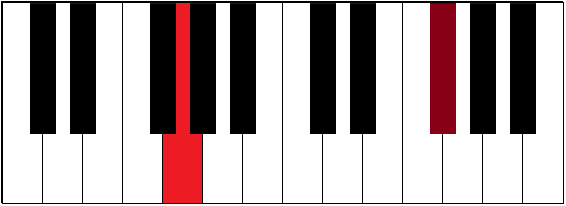

Now, this is not only true for the ‘perfect 5th-perfect 4th pair’. Other pairs of intervals exist that act the same way. In fact, every interval has its inversion. For example, the inversion of the major 3rd interval from –let’s say- E to G# is the minor 6th interval from G# to E. Also here, the intervals add up to an octave, because 4 semitones (major 3rd) plus 8 semitones (minor 6th) equals 12 semitones (an octave).

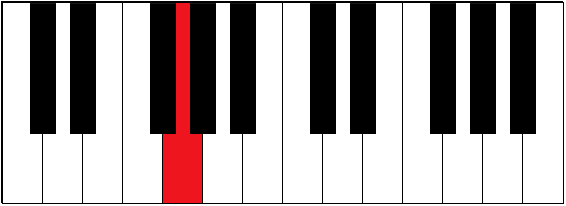

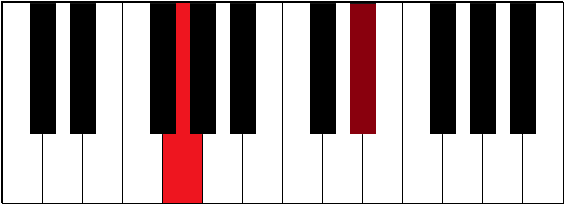

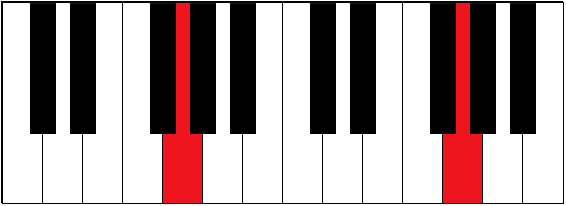

A special case is the tritone interval. The tritone doesn’t need a partner, it just needs itself! A tritone splits an octave exactly in two equal parts, so a tritone just needs another tritone to make an octave.

A tritone consists of 6 semitones, so: 6+6=12, an octave!

Here’s a list of intervals with their inversions:

| Intervals with their inversion: |

| Perfect unison + perfect octave

Semitone (or minor second) + major seventh Whole tone (or major second) + minor seventh Minor third + major sixth Major third + minor sixth Perfect fourth + perfect fifth Tritone + tritone |

Notice that a perfect interval always goes together with another perfect interval and a minor interval always goes together with a major interval (and, of course, vice versa).

Please leave a comment below and tell us what you think of this lesson.

Note interval | Minor and Major Intervals | Intervals

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

When you play 2 different notes at the same time or one after the other, you will have a lower and a higher note. This means there is a distance (in pitch) between the 2 notes. This distance is called the interval between the 2 notes, the note interval, or simply interval.

You can measure this intervals between notes in number of semitones, and this takes us directly to our first interval: the semitone.

The semitone

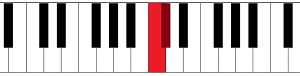

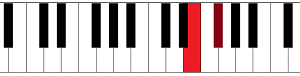

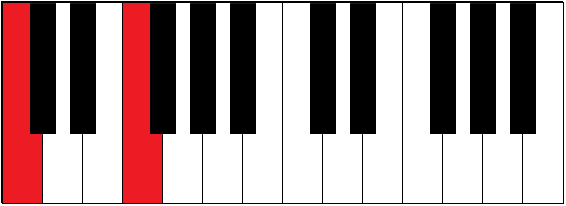

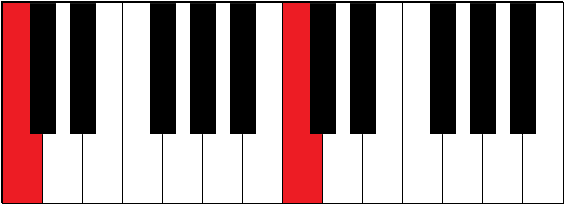

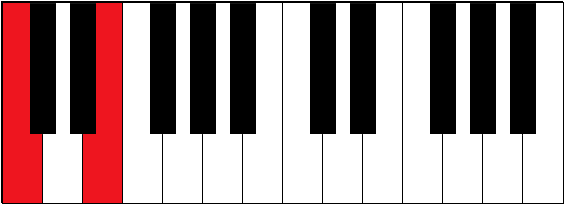

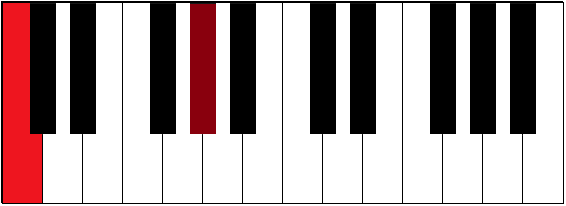

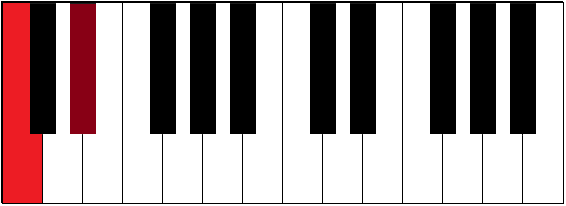

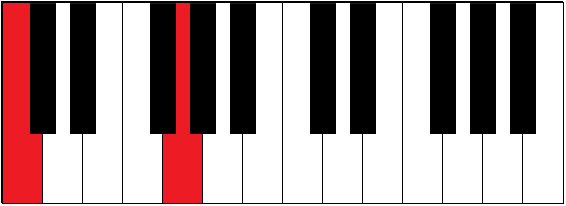

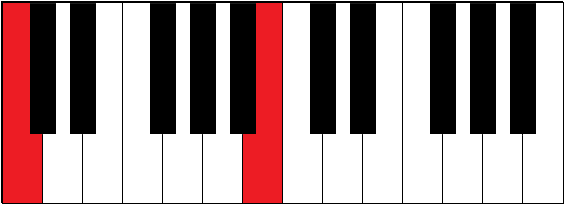

The easiest way to explain semitones is to look at the piano keyboard. A semitone is the interval from a key on the keyboard to the first note at the left or the right. So, for example, the interval from C to C# (or Db) in the next figure is a semitone.

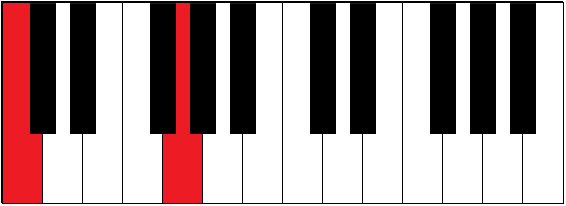

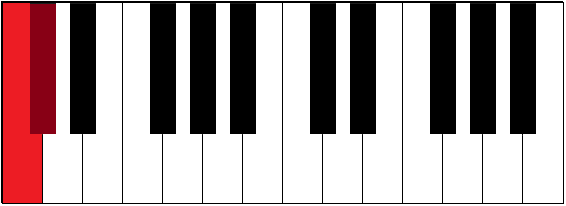

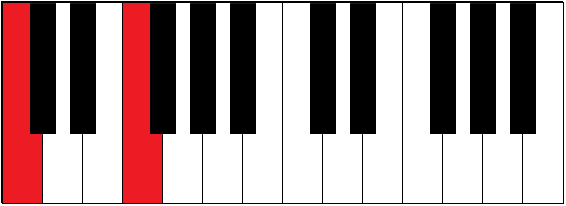

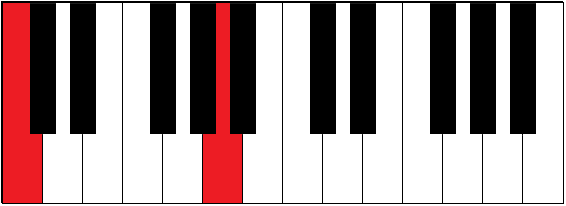

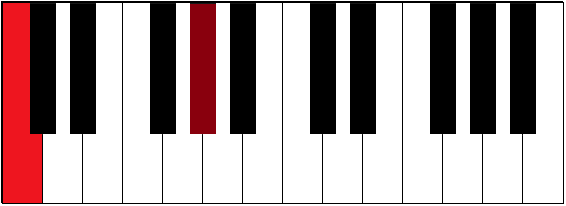

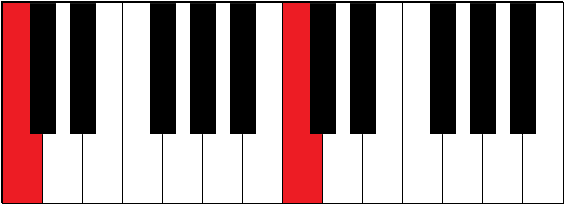

Or, for example from G# (or Ab) to A:

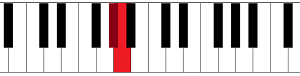

It’s also possible to have a semitone between 2 white keys; this is the case between E and F and between B and C:

Notice that it’s not possible to have an interval of a semitone between 2 black keys on the piano.

Other names for a semitone are: half tone or half step.

The whole tone

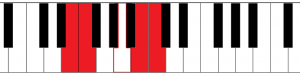

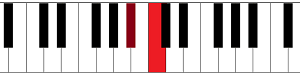

The whole tone, or also called whole step, is an interval that consists of 2 semitones. Here are some examples of a whole tone:

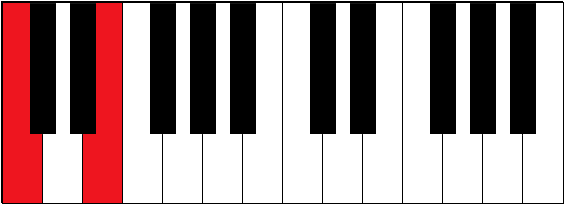

From C to D:

From F# (or Gb) to G# (or Ab):

From E to F# (or Gb):

From Bb (or A#) to C:

Intervals from C to other ‘white key-notes’

Let’s take a look at the intervals from C to the other white keys on the piano up till the next C. Those notes are the notes from the C major scale (as you will learn later).

- When we call C the first note, D the second note, E the third note and so on, then the interval from C to the second note (D) is simply called ‘second’. The interval from C to the third note (E) is called ‘third’. And so on…

- The interval from C to the eighth note (C) is not called ‘eighth’, but ‘octave’.

- The interval from C to itself is called ‘’unison’.

In the table below, you can see an overview of all those intervals:

Note 1: the interval from C to D is not called ‘whole tone’ in this table, because ‘whole tone’ is actually an alternative name, where ‘second’ is more an official name. However, ‘whole tone’ is used more often than ‘second’.

Note 2: it might seem strange to call the unison an interval, since there is no distance between a note and itself. You could however call this a distance of 0 (semitones).

| Interval on piano keyboard: | Interval between the notes: | Distance in (whole) tones: | Name of the interval: |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-C | 0 | unison |

| C-D | 1 | second |

| C-E | 2 | third |

| C-F | 2½ | fourth |

| C-G | 3½ | fifth |

| C-A | 4½ | sixth |

| C-B | 5½ | seventh |

| C-C | 6 | octave |

All the intervals from C

Let’s also include in the table the intervals from C to the notes on black keys on the piano.

To do so, we have to introduce perfect intervals, major intervals and minor intervals.

Actually, in the table above, the unison, the fourth, the fifth and the octave are all perfect intervals. So, we speak of the perfect unison, the perfect fourth, and so on (even if we often omit the term ‘perfect’, and we just say unison, fourth, … etcetera).

All the other intervals in the table above are major intervals, so: major second, major third, major sixth and major seventh. The minor intervals will appear between C and the ‘black notes’ (table below).

In order to complete the table below, we have to follow the next rules:

- When a major interval is reduced by a half tone, it becomes a minor interval (this is not possible for a perfect interval). For example, when a major 3rd interval (C-E) is reduced by a half tone, it becomes a minor 3rd interval (C-Eb).

- Perfect intervals and minor intervals can be reduced by a half tone, they then become diminished intervals. For example, when a perfect 5th (C-G) is reduced by a half tone, it becomes a diminished 5th (C-Gb).

- Perfect intervals and major intervals can be increased by a half tone, they then become augmented intervals. For example, when a perfect 5th (C-G) is increased by a half tone, it becomes an augmented 5th (C-G#).

The table below can be scrolled horizontally (under the table).

| Interval on piano keyboard: | Interval between the notes: | Distance in number of (whole) tones | Interval name (perfect/major/minor): | Interval name (diminished/ augmented): | Alternative name(s): |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-C | 0 | perfect unison | ||

| C-C# | ½ | augmented unison | half tone, semitone, half step | |

| C-Db | ½ | minor second | half tone, semitone, half step | ||

| C-D | 1 | major second | whole tone, whole step | |

| C-D# | 1½ | augmented second | ||

| C-Eb | 1½ | minor third | |||

| C-E | 2 | major third | ||

| C-F | 2½ | perfect fourth | ||

| C-F# | 3 | augmented fourth | tritone | |

| C-Gb | 3 | diminished fifth | tritone | ||

| C-G | 3½ | perfect fifth | ||

| C-G# | 4 | augmented fifth | ||

| C-Ab | 4 | minor sixth | |||

| C-A | 4½ | major sixth | ||

| C-A# | 5 | augmented sixth | ||

| C-Bb | 5 | minor seventh | |||

| C-B | 5½ | major seventh | ||

| C-C | 6 | perfect octave |

Now, I can imagine that all this looks quite difficult, especially when you’re a beginner and you see all those interval names for the first time.

In that case: don’t worry: we will, especially in the beginning, not use all those interval names. So don’t start learning the table above by heart, but limit yourself to the next intervals:

- Half tone (also called: semitone or half step)

- Whole tone

- Minor 3rd

- Major 3rd

- Perfect 4th

- Perfect 5th

- Major 6th

- Minor 7th

- Major 7th

- Perfect octave

And, as I said before, I normally speak of the 4th, 5th and octave and not of perfect 4th, perfect 5th and perfect octave.

When you start learning about diminished chords, you should also know what a diminished 5th and a diminished 7th is, but that’s for later…

Note: We normally call the notes after their interval they make with the root (the root is the starting note, in our example the root is the note C (you will learn more about this in the major scales)). So, when the root is C, then the note E is called the major 3rd. So, ‘major 3rd’ is then not only the name of the interval (from C to E), but also of the note E (but only when the root is C!).

Intervals from another root note than C

Till now, we’ve only seen the intervals in the C major scale, so intervals from the root note C. How does this work in other major scales, or said in another way: how does this work from another root note than C?

Let me take as an example the root note G. So, we’re then looking for all the intervals from G to other (white and black) notes up till the next G an octave higher.

When you already know how major scales ‘work’, you can simply look at the G major scale: from G to the second note of the G major scale (A) is the major 2nd, from G to the third note of the G major scale the major 3rd, to the fourth note the perfect 4th, and so on… Watch out: the major 7th is now on a black key, the F#.

When you still don’t know how major scales ‘work’, then just look at the number of tones in the second table and apply that from the note G.

The result is shown in the table below:

The table below can be scrolled horizontally (under the table).

| Interval on the piano keyboard: | Interval between the notes: | Distance in number of (whole) tones: | Interval name (perfect/major/minor): | Interval name (diminished/ augmented): | Alternative name: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-G | 0 | perfect unison | ||

| G-G# | ½ | augmented unison | half tone, semitone, half step | |

| G-Ab | ½ | minor second | half tone, semitone, half step | ||

| G-A | 1 | major second | whole tone, whole step | |

| G-A# | 1½ | augmented second | ||

| G-Bb | 1½ | minor third | |||

| G-B | 2 | major third | ||

| G-C | 2½ | perfect fourth | ||

| G-C# | 3 | augmented fourth | tritone | |

| G-Db | 3 | diminished fifth | tritone | ||

| G-D | 3½ | perfect fifth | ||

| G-D# | 4 | |||

| G-Eb | 4 | minor sixth | |||

| G-E | 4½ | major sixth | ||

| G-E# | 5 | augmented sixth | ||

| G-F | 5 | minor seventh | |||

| G-F# | 5½ | major seventh | ||

| G-G | 6 | perfect octave |

One further step

When you’re already more advanced in music (theory) and you want to know more about intervals, then keep reading. When you’re a beginner, then just scroll down to the bottom of this page where you will find interactive exercises about intervals.

In the first lesson (about note names) I told you already something about double sharps and double flats.

As you know, C and Dbb are the same note on the piano. Does this mean that the interval between C and Dbb is the same interval as the interval between C and C, so a unison?

No. The interval from C to Dbb is not called a unison. We call this interval a diminished 2nd.

But why second? This is because Dbb is based on the note D: it is a D that has been lowered twice by a half tone: From C to D is a major 2nd, from C to Db a minor 2nd, so from C to Dbb a diminished 2nd.

Now, to be honest: you will almost never see the name ‘diminished 2nd’, but officially it exists.

But, for example a diminished 7th occurs often in music, for example in the C diminished chord. A diminished 7th is a half tone lower than a minor 7th, so a half tone lower than Bb (when C is the root note). This makes the diminished 7th in the key of C the note Bbb, which is on the piano the same note as the A.

We can now extend our table as follows (from the root C):

The table below can be scrolled horizontally (under the table).

| Interval on the piano keyboard: | Interval between the notes: | Distance in number of (whole) tones: | Interval name (perfect/major/minor): | Interval name (diminished/ augmented): | Alternative name: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-C | 0 | perfect unison | ||

| C-Dbb | 0 | diminished second | |||

| C-C# | ½ | augmented unison | half tone, semitone, half step | |

| C-Db | ½ | minor second | half tone, semitone, half step | ||

| C-D | 1 | major second | whole tone, whole step | |

| C-Ebb | 1 | diminished third | whole tone, whole step | ||

| C-D# | 1½ | augmented second | ||

| C-Eb | 1½ | minor third | |||

| C-E | 2 | major third | ||

| C-Fb | 2 | diminished fourth | |||

| C-E# | 2½ | augmented third | ||

| C-F | 2½ | perfect fourth | |||

| C-F# | 3 | augmented fourth | tritone | |

| C-Gb | 3 | diminished fifth | tritone | ||

| C-G | 3½ | perfect fifth | ||

| C-Abb | 3½ | diminished sixth | |||

| C-G# | 4 | augmented fifth | ||

| C-Ab | 4 | minor sixth | |||

| C-A | 4½ | major sixth | ||

| C-Bbb | 4½ | diminished seventh | |||

| C-A# | 5 | augmented sixth | ||

| C-Bb | 5 | minor seventh | |||

| C-B | 5½ | major seventh | ||

| C-Cb | 5½ | diminished octave | |||

| C-B# | 6 | augmented seventh | ||

| C-C | 6 | perfect octave |

It’s very practical to be able to quickly recognize intervals. For that reason, I advice to do the exercises below.

Recommended exercises for note interval

How to form a major scale

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

For piano players, the C major scale is the easiest major scale because it starts on C and consists of all the white notes up to the next C. So, the notes of the C major scale are: C D E F G A B C (this looks as if the scale has 8 notes, but since the C is played twice, the scale consists of 7 different notes).

Let’s now look at the intervals between its consisting notes:

- From C to D: whole tone (W)

- From D to E: whole tone (W)

- From E to F: half tone (H)

- From F to G: whole tone (W)

- From G to A: whole tone (W)

- From A to B: whole tone (W)

- From B to C: half tone (H)

So the intervals between the consecutive notes of the C major scale are:

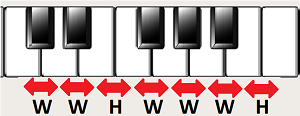

W W H W W W H (see figure)

Since all major scales sound the same way, this structure is valid for all major scales. That means that the only difference between all major scales is their root (starting note). So we can use this structure to find out all the other major scales. Let me illustrate this with some examples:

The D major scale

Let’s apply our ‘formula’ (W W H W W W H) to find the scale of D major.

- From D, a whole tone (W) up to E

- From E, a whole tone (W) up to F#

- From F#, a half tone (H) up to G

- From G, a whole tone (W) up to A

- From A, a whole tone(W) up to B

- From B, a whole tone (W) up to C#

- From C#, a half tone (H) up to D

So, the notes of the D major scale are: D E F# G A B C# D

Now, why did I call the 3rd and 7th notes F# and C# and not Gb and Db? Well, this is because we have to apply one of the following 2 rules (you can choose which rule to apply, since one rule implies automatically the other):

- Don’t use the same letter for 2 consecutive notes

- Don’t leave a ‘gap’ between 2 consecutive notes

Let me explain those rules:

Don’t use the same letter for 2 consecutive notes: Imagine that in the D major scale, I would have used Gb instead of F#. The first 4 notes of the scale would then have been: D E Gb G …

In this case, the letter G is used twice (even if the first has a flat sign), so this is against our first rule.

In the same way, you can show that you have to use C# instead of Db.

Don’t leave a gap between 2 consecutive notes: Again, imagine I would have used Gb instead of F# in the D major scale, so: D E Gb G …

Now, between E and Gb, there’s a ‘gap’ because we miss the letter F. We have therefore to use the letters in the order as they appear on the white keys of the piano keyboard.

The F major scale

When we apply our formula to find the F major scale, we get:

- From F, a whole tone up to G

- From G, a whole tone up to A

- From A, a half tone up to Bb

- From Bb, a whole tone up to C

- From C, a whole tone up to D

- From D, a whole tone up to E

- From E, a half tone up to F

Did you notice that the scale of F major has a flat note (the Bb), not a sharp? It cannot be an A# (just apply one of the rules mentioned above and you will see that the 3rd note in the scale of F major is a Bb, not an A#).

So, the scale of F major is: F G A Bb C D E F

The other major scales

With our formula (WWHWWWH), you can now find out yourself the other major scales. Since there are 12 different notes, that means that there are also 12 major scales.

When you do the scales in the order as listed below, you will see that each time you will get one more sharp in the scale. Starting from the C major scale (0 sharps), move on to the G major scale (1 sharp), then the D major scale (2 sharps, as you have already seen before), etcetera, till you reach the scale of F# (6 sharps). And don’t forget to apply one of the 2 rules (don’t repeat letters & don’t leave gaps). At the end of this lesson you will find the right solutions.

Order for the major scales with sharps:

C major (0 sharps)

G major (1 sharp)

D major (2 sharps)

A major (3 sharps)

E major (4 sharps)

B major (5 sharps)

F# major (6 sharps)

Notice that in the list above, we go up a 5th in every step. So, starting with C major, every time you go up a 5th, the major scale gets one more sharp.

When done, then go to the list of major scales with flats.

Starting with C, every time you go a 5th down, you will get one more flat in the scale. So the list for the major scales with flats is:

C major (0 flats)

F major (1 flat)

Bb major (2 flats)

Eb major (3 flats)

Ab major (4 flats)

Db major (5 flats)

Gb major (6 flats)

Btw, instead of saying a 5th down, I could also have said a 4th up, this is explained in the lesson characteristics of intervals.

You might have noticed that the two lists have together 14 items. That’s strange, because there are only 12 different notes, so also 12 different major scales. Well, as you can see, the C is repeated, so this eliminates already 1 item. When you look well at both lists, you can also see that the last item in list 1 is exactly the same as the last item in list 2: F# and Gb are enharmonic equivalent notes. So they are exactly the same note, only written differently. When you found the right notes for both major scales, you will see that they consist of exactly the same notes, but written as their enharmonic equivalents.

All the major scales (solutions)

It’s time to check if you found the right major scales, so first the table with the major scales with sharps:

| Root

(first note) |

Notes of the major scale |

| C | C D E F G A B C |

| G | G A B C D E F# G |

| D | D E F# G A B C# D |

| A | A B C# D E F# G# A |

| E | E F# G# A B C# D# E |

| B | B C# D# E F# G# A# B |

| F# | F# G# A# B C# D# E# F# |

And now the table with the major scales with flats:

| Root

(first note) |

Notes of the major scale |

| C | C D E F G A B C |

| F | F G A Bb C D E F |

| Bb | Bb C D Eb F G A Bb |

| Eb | Eb F G Ab Bb C D Eb |

| Ab | Ab Bb C Db Eb F G Ab |

| Db | Db Eb F Gb Ab Bb C Db |

| Gb | Gb Ab Bb Cb Db Eb F Gb |

Compare the F# major scale from the first table with the Gb major scale from the second table: both scales are exactly the same, the notes are only written differently.

Note also the E#, which is enharmonic equivalent with F, and the Cb, the enharmonic equivalent of B.

Other enharmonic equivalent scales

You might have asked yourself: “Why are the Gb and F# scales listed as enharmonic equivalent scales and not for example Db and C#, or Ab and G#? Why are only the ‘flat scales’ listed?”

You will understand this better with the circle of fifths, but the short answer is: “Of course, you can make the C# major scale, the G# major scale and so on, but they have so many sharps (even double sharp notes), that they become difficult to handle.” What would you prefer? The Ab major scale with 4 flats, or the G# major scale with 8 sharps? I think the choice is not so difficult…

It’s of very big importance to know well your major scales. It will help you with all the other music theory if you can quickly come up with the right scale in all the 12 different keys. For that purpose, it’s important to practice a lot. The exercise below is an excellent way to practice your major scales.

Recommended exercises for all major scales

Place the notes of a major scale on the piano

I hope that you learned a lot in this lesson about major scales and that the exercise helped you to quickly master the scales in all 12 keys.

Please tell us what you think of this lesson and the exercise by leaving a comment below.