Sharps and flats – Key signature

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

In the treble clef and bass clef lessons, you learned how to read and write the ‘white key notes’, the ones without sharps or flats; how to write sharps and flats in sheet music?

Sharps and flats

How to write a sharp note in a staff? It’s really simple: just put the sharp sign (#) before the note.

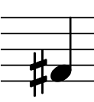

For example, this is an F#:

And this is a D#:

For a flat note, just write the flat sign (b) before the note:

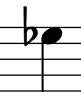

This is a Gb:

And this is an Eb:

Important is that this sharp or flat sign is only valid from the moment the sign is displayed till the end of the measure you’re in. In the next example, I’ll explain this in more detail (btw, the staff is in treble clef):

The notes in the first measure are: F# G A F#. So, the last note in the first measure is an F#, not an F. The notes in the second measure are: F G A F. The sharp sign from the first measure is not anymore valid in the second measure.

But what if I wanted to have F# G A F in the first measure? In that case, we have the natural sign, that cancels the sharp sign before the first note:

The same rule applies to flat notes. The flat sign is only valid within the measure where it is used. If we want to cancel the flat sign for a certain note in the same measure, you can apply the same natural sign as with the sharp notes.

Key signature

Have a look at the next melody, which is in the key of F major:

You see that the melody has one flat note, the Bb. That’s normal, since F major has a flat note in its scale, the Bb!

You would expect this Bb to occur even more often in the melody. And that’s exactly what happens, have a look at the next line in this song:

When I would display also the rest of the song, you would see even more B flats appear.

Wouldn’t it be much easier to say at the beginning of the song that every B should be seen as a Bb? Well, that’s exactly what is normally done. We put the flat sign in the beginning, between the clef and the time signature. Now, the same song can be displayed as follows:

Note that not only B’s that are on the 3rd line of the staff become Bb’s. All the B’s become Bb’s, so also this one.

Sharps and flats that are displayed between the clef and the time signature, are called the key signature.

The key signature corresponds with the major or minor key the song is in. When a song is in G major, which, as you know, has only one sharp (the F#), the key signature looks as:

The key signature corresponds with the major or minor key the song is in. When a song is in G major, which, as you know, has only one sharp (the F#), the key signature looks as:

Now, the same key signature also applies to E minor, since E minor is the relative minor of G major. So, every key signature can be used for a major key and its relative minor key.

Other key signatures

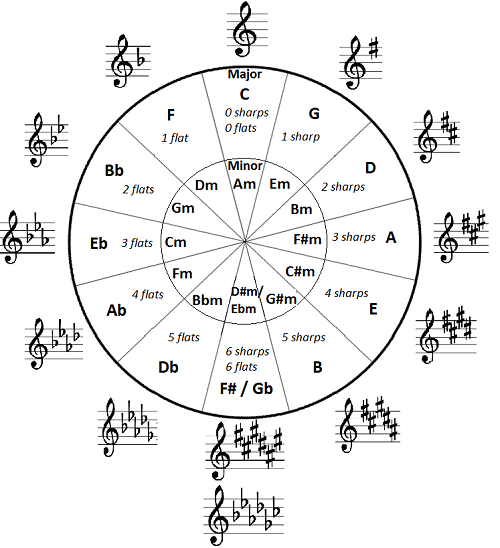

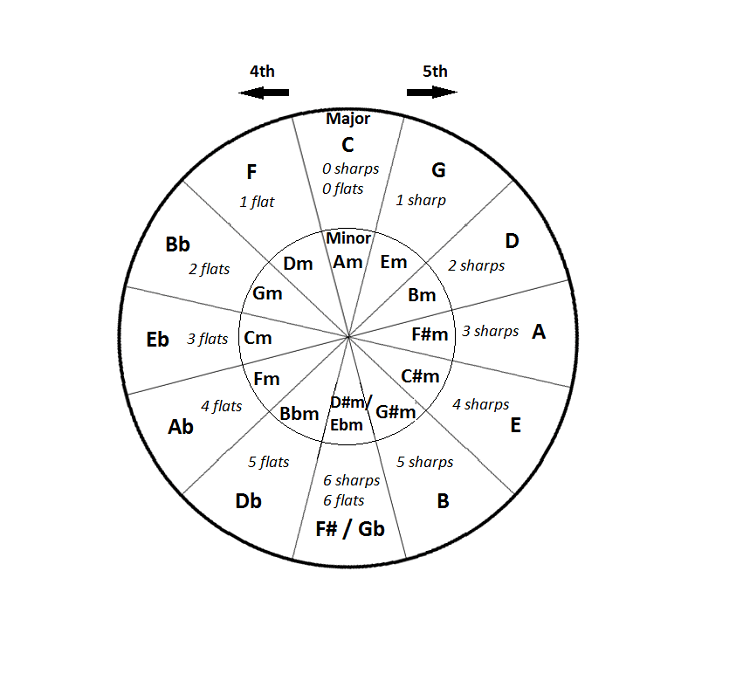

We can display the key signatures for all major and minor keys in the circle of fifths. This gives us a nice and quick overview of all the sharps and flats in the major and minor keys:

Now that you know about sharps, flats and key signatures, check your knowledge with the quiz that is accesible via the link below:

Recommended exercises for sharps and flats:

Final music reading exercise – Level I

Please let us know if this lesson helped you in learning about sharps, flats and key signatures by leaving a comment below.

How to form a natural minor scale

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

First of all, why do I say ‘natural minor scale’, and not simply ‘minor scale’ (I also called a major scale just ‘major scale’ without any other specification)?

This is, because there exists only one type of major scales, but there are 3 types of minor scales:

- the natural minor scale

- the harmonic minor scale

- the melodic minor scale

In this lesson, we talk only about the natural minor scale, in another lesson, I will talk about the other 2 minor scales.

The natural minor scale

When you know how to form a major scale, it’s very simple to form a natural minor scale. Before telling you the general rule, let me first show you this with an example:

In this example I will show you how to form the A natural minor scale. Well, as I promised, it’s very simple: the notes of the A natural minor scale are exactly the same as the notes of the C major scale, so only the white keys on the piano.

So the A natural minor scale is:

A B C D E F G A

The only difference is the starting note, the root: A natural minor starts on an A, where C major starts on a C. And that’s all! Simple, isn’t it?

Since A natural minor and C major share the same scale (only another starting note), we say that ‘A minor is the relative minor of C major’ and ‘C major is the relative major of A minor’.

Now, every minor scale has its relative major scale, so the question now is: “How to find out which relative major scale belongs to a natural minor scale?”

Well, when you look at A minor/C major, you see that from A, when you go up a minor 3rd, you arrive at C.

So, when you want to find out –for example- what the C natural minor scale is, you have to go up a minor 3rd from C. A minor 3rd up from C brings us to Eb.

Eb major is the relative major of C minor and so they share the same scale. This means that the C natural minor scale is:

C D Eb F G Ab Bb C

The other natural minor scales

As an exercise, you could now try to find out all the other natural minor scales. The best way to start is perhaps with our list of major scales. Then start with a certain major scale, find its relative minor, and start on the root of that relative minor scale and you’re done.

For example: start with the Db major scale. What’s the relative minor of Db major? Well, now you have to go down a minor 3rd!

A minor 3rd (3 semitones) down takes us to Bb (not A#, because in the scale of Db, it’s a Bb).

Another way to find the relative minor of a major scale is to look at the 6th note in the major scale: remember that the relative minor of C major was A minor. Well, A is the 6th note in the scale of C major.

OK, try to see if you can find the other natural minor scales. You will find the solutions just here below:

Tables with all the natural minor scales

First, the table with sharps:

| Major scale | Relative minor | Natural minor scale | Number of sharps |

| C | Am | A B C D E F G A | 0 |

| G | Em | E F# G A B C D E | 1 |

| D | Bm | B C# D E F# G A B | 2 |

| A | F#m | F# G# A B C# D E F# | 3 |

| E | C#m | C# D# E F# G# A B C# | 4 |

| B | G#m | G# A# B C# D# E F# G# | 5 |

| F# | D#m | D# E# F# G# A# B C# D# | 6 |

Followed by the table with flats:

| Major scale | Relative minor | Natural minor scale | Number of flats |

| C | Am | A B C D E F G A | 0 |

| F | Dm | D E F G A Bb C D | 1 |

| Bb | Gm | G A Bb C D Eb F G | 2 |

| Eb | Cm | C D Eb F G Ab Bb C | 3 |

| Ab | Fm | F G Ab Bb C Db Eb F | 4 |

| Db | Bbm | Bb C Db Eb F Gb Ab Bb | 5 |

| Gb | Ebm | Eb F Gb Ab Bb Cb Db Eb | 6 |

Notice that the D# natural minor scale (6 sharps) and the Eb natural minor scale (6 flats) are the same scales, only written differently (they are enharmonic equivalent).

Now, it’s important to practice the natural minor scales. I advice you to do the exercise below.

Recommended exercises for natural minor scales

Place the notes of a natural minor scale on the piano

Please tell us what you think of the natural minor scale lesson and the exercise by leaving a comment below.

The circle of fifths

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

The circle of fifths (also called cycle of fifths) gives us a handy overview of the different scales and how they are related to each other.

How to form the circle of fifths

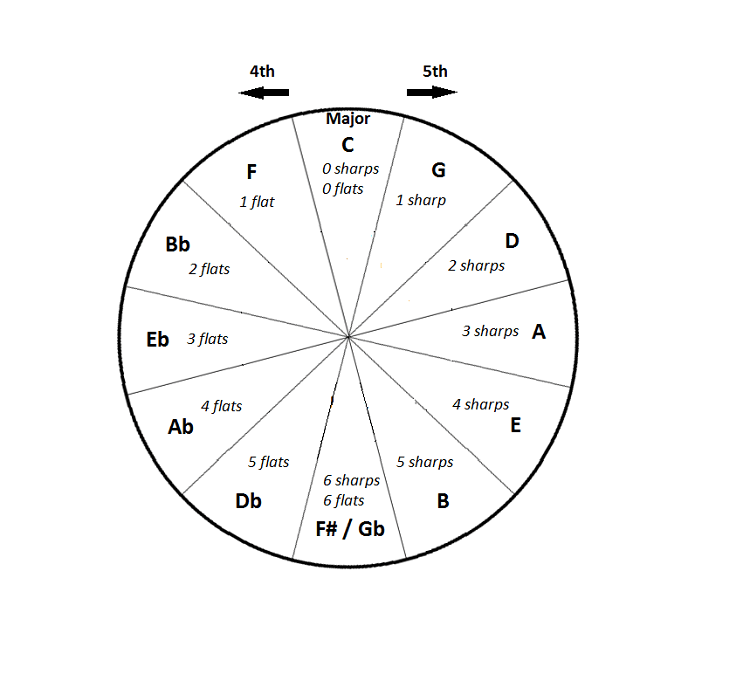

In the lesson ‘How to form a major scale’, I explained that starting from the C major scale, every time we take a major scale a fifth higher, the scale gets one extra sharp note. And, starting from C major, every time we go a fifth down (or a fourth up, which is basically the same), we get one more flat note in the major scale.

We could now display all the roots (starting notes) of the major scales in a row with C major (no sharps, no flats) in the middle. At the left of C, all the major scales with flats. Every step to the left would mean a fifth down (or a fourth up) and thus an extra flat note in the scale. At the right of C, all the major scales with sharps. Every step to the right would mean a fifth up (or a fourth down) and thus an extra sharp note in the scale.

Gb Db Ab Eb Bb F C G D A E B F#

It is important to realize that the most left scale (Gb) and the most right scale (F#) are actually the same scale, since Gb and F# are the same note, only written differently: they are enharmonic equivalent.

So that means that we could display this row with scales in a circle, as follows:

At the right side we have the major scales with sharps, on the left side the major scales with flats.

Every step clockwise in this circle (this would correspond with a step to the right in our row above) means a fifth up (or a fourth down). And every step counterclockwise a fifth down (or a fourth up). That’s why we call this circle the ‘circle (or cycle) of fifths’. Since a fifth up corresponds with a fourth down and vice versa, this circle is sometimes also called the ‘circle (or cycle) of fourths.

The minor scales in the circle of fifths

Since a natural minor scale has exactly the same notes as its relative major scale, we can also put the natural minor scales in our circle of fifths. So, for example: since the A minor scale and the C major scale share the same notes, we can put them in the same place in the circle of fifths:

And see here our circle of fifths, which gives us a quick overview of the number of sharps and flats in every major and minor scale, plus an overview of relative minor/major relationships.

Why would I need a circle of fifths?

As mentioned above, the circle of fifths gives a good overview of sharps/flats and relative minor/major.

The circle of fifths is among other things very handy for example in transposing a song (I’ll come back on this in a later lesson).

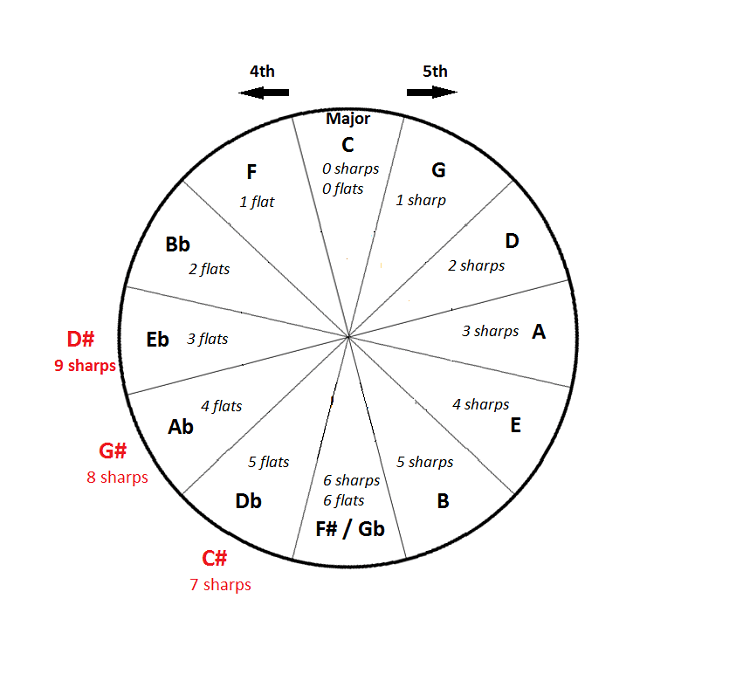

The circle of fifths also quickly shows us why the major scales that start on a black key on the piano are mostly written with flats instead of with sharps. Let me illustrate this with the Eb major scale, which has 3 flats.

Eb is enharmonic equivalent with D#, so let’s look how the D# major scale looks like. First of all, in the circle of fifths, from F# I will go on clockwise to C#, G# and then to D# (so every step a fifth up). You can see that D# major has 9 sharps (wow!).

Let’s, for fun, see how the D# major scale looks like (see also the lesson ‘How to form a major scale’):

From D#, a whole tone (W) up to E#

From E#, a whole tone (W) up to F## (or Fx)

From F##, a half tone (H) up to G#

From G#, a whole tone (W) up to A#

From A#, a whole tone (W) up to B#

From B#, a whole tone (W) up to C## (or Cx)

From C##, a half tone (H) up to D#

So the D# major scale is:

D# E# F## G# A# B# C## D#

As you can see: a total of 9 sharps (don’t count the D# twice)!

Compare this with the Eb major scale:

Eb F G Ab Bb C D Eb

Now, my question to you is: “Which scale do you prefer, the Eb major scale, or the D# major scale?” I think I know the answer… 🙂

Please tell us what you think of this lesson by leaving a comment below.

What are scales? Major scale vs minor scales

You can watch this lesson in the video below, or read at your ease under the video.

What are scales? How can you hear the difference between a major scale and a minor scale?

What are scales?

Let’s start with the first question: what are scales?

A scale is a set of notes (usually 7 different notes) that you can play in ascending order, descending order or in any other order.

You can define a certain scale by the intervals between its consisting notes.

As you will see later, the scale determines the mood of the music.

The difference between a major scale and a minor scale

As I said before, a scale sets the mood of the music. Below, you can listen to the C major scale played in ascending order over a C major chord.

And now, here below, listen to the C (natural) minor scale played in ascending order over a C minor chord.

Did you hear the difference? The major sound is much happier, the minor sound is more sad, tragic or melancholic.

Notice that both scales start on a (low) C and end on a (high) C and consist of 7 different notes (you hear a sequence of 8 notes, but the C is played as the first and lowest note and as the last and highest note, so twice). So the only difference between both scales are the intervals between their consisting notes.

I hope you liked this mini-lesson about the difference between major and minor harmony. Please tell us what you think of this lesson by leaving a comment below.